The Anunnaki: Decoding Ancient Mesopotamian Divine Councils

Separating Historical Facts from Modern Fiction

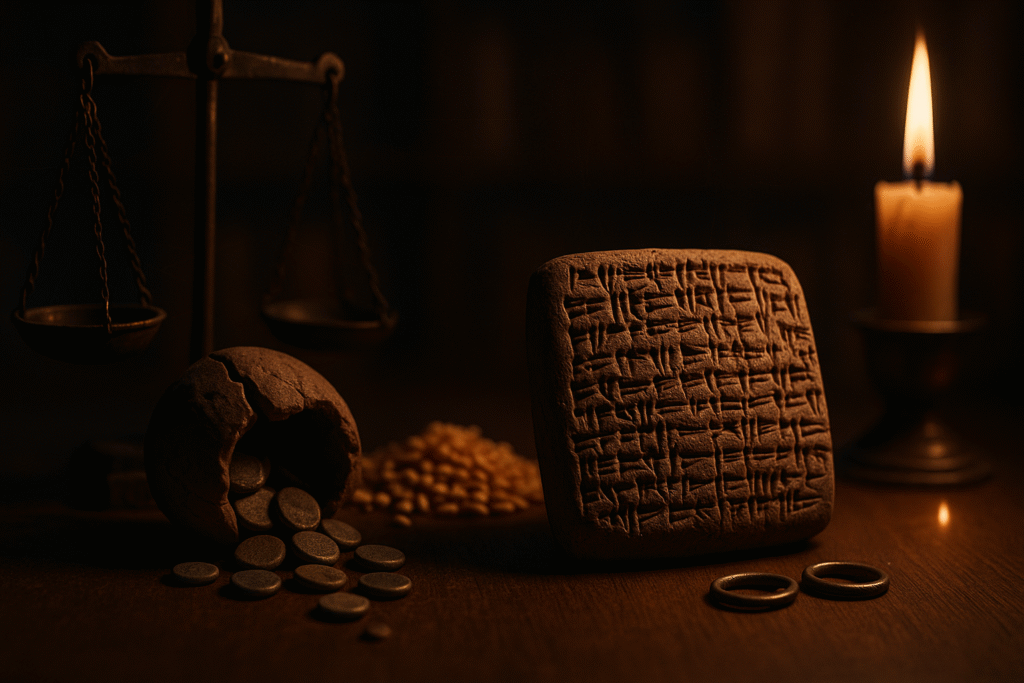

For over four millennia, cuneiform tablets buried in the sands of Mesopotamia have preserved one of humanity’s earliest theological concepts: the Anunnaki. These divine figures, whose names appear across hundreds of ancient texts, have captured modern imagination—sometimes in ways their original authors never intended. By examining the archaeological record with scholarly precision, we can separate historical understanding from contemporary speculation and discover what these ancient peoples actually believed about divine governance.

Understanding the Ancient Context

The term “Anunnaki” emerges from a civilization that gave us writing, the wheel, and the first cities. Between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, Sumerian and later Akkadian scribes developed sophisticated theological frameworks that would influence religious thought across the ancient Near East. Within this context, the Anunnaki represented far more than a simple pantheon—they embodied an entire philosophy of cosmic order.

Archaeological evidence reveals that Mesopotamian religious practice was remarkably diverse, varying significantly between city-states and evolving across centuries. This flexibility extended to divine categorizations, including the Anunnaki themselves. Rather than representing a fixed group with unchanging membership, the term functioned as a flexible category that adapted to local needs and changing theological understanding.

The Fluid Nature of Divine Categories

One of the most striking features of Anunnaki references in cuneiform literature is their variability. Where modern readers might expect consistency—a definitive list of members with clearly defined roles—ancient texts reveal something far more sophisticated. The An = Anum god-lists from different periods and locations provide varying rosters, sometimes naming four Anunnaki, sometimes seven or more, occasionally different deities entirely.

This variation was not evidence of confusion or corruption in the textual tradition. Rather, it reflected the living, breathing nature of Mesopotamian religious practice. Local temples, regional political considerations, and evolving theological thought all influenced how scribes understood and recorded divine hierarchies. The function of the Anunnaki—as councils that deliberated, decreed, and maintained cosmic order—remained consistent even as their membership shifted.

Consider, for instance, how the same divine figure might appear as an Anunnaki in one city’s texts while being categorized differently elsewhere. This flexibility allowed local priesthoods to adapt universal theological concepts to their particular circumstances while maintaining connection to broader Mesopotamian religious tradition.

Divine Assemblies and Cosmic Governance

Primary sources consistently portray the Anunnaki as deliberative bodies rather than individual actors. In the Epic of Gilgamesh, they appear as a council weighing momentous decisions. The Atrahasis epic presents them as divine legislators whose decrees shape human destiny. Across these varied literary contexts, their role as cosmic judges and administrators remains constant.

This portrayal reflects sophisticated political thinking. Ancient Mesopotamian societies developed complex governmental structures—city councils, royal courts, administrative hierarchies—and their religious imagination naturally incorporated similar organizational principles. The Anunnaki represented divine governance that paralleled and legitimized earthly authority structures.

Descent myths, particularly Inanna’s Descent to the Netherworld, present the Anunnaki as underworld judges who determine fates after death. Here, their function as arbiters extends beyond earthly concerns to cosmic justice. The imagery is vivid: seven judges seated in solemn assembly, their eyes like death, their word final. This literary treatment emphasizes the gravity and permanence of divine judgment.

Labor, Creation, and Social Memory

The Atrahasis creation narrative provides crucial insight into how Mesopotamian thinkers understood the relationship between divine and human labor. In this account, the Igigi gods (often associated with or overlapping the Anunnaki in function) rebel against excessive toil imposed by higher deities. The creation of humanity emerges as a solution to this divine labor dispute—humans serve in temples and maintain offerings, allowing the gods to rest.

Modern interpretations sometimes read this narrative literally, seeking historical events behind mythological language. However, approaching these texts as theological and social commentary reveals their true sophistication. The creation story encodes ancient thinking about why religious institutions exist, why kings require divine legitimation, and how human society should relate to cosmic order.

The narrative structure suggests that Mesopotamian thinkers understood social hierarchy as divinely ordained but not arbitrarily imposed. Both gods and humans have roles to play in maintaining cosmic stability, and the temple system represents this mutual obligation made concrete. Royal inscriptions frequently invoke Anunnaki approval precisely because effective kingship required divine sanction to maintain social order.

Misreadings and Modern Interpretations

Contemporary popular treatments of Anunnaki mythology often fundamentally misunderstand the nature of ancient religious literature. Approaches that treat ritual language as technological description, metaphors as literal reporting, or literary devices as historical records miss the sophisticated ways these texts functioned in their original contexts.

Ancient hymns, prayers, laments, and mythological narratives employed highly stylized language that served specific religious and social functions. When the Descent of Inanna describes divine radiance or supernatural abilities, it participates in established literary conventions designed to evoke awe, teach moral lessons, or facilitate ritual experience. Reading such passages as technological reports strips away their intended meaning and reduces complex theological thinking to crude materialism.

The interpretive error extends beyond individual passages to entire methodological approaches. Ancient astronaut theories, for instance, consistently ignore genre distinctions that were crucial to how these texts functioned. A royal inscription praising divine favor operates according to different literary rules than a creation myth exploring cosmic origins, which differs again from a ritual incantation designed for ceremonial performance. Collapsing these distinctions produces readings that would have been foreign to ancient practitioners themselves.

Archaeological and Textual Evidence

The cuneiform record provides abundant evidence for how ancient peoples actually understood the Anunnaki. Royal inscriptions from Mesopotamian rulers consistently invoke Anunnaki approval as legitimation for political authority. Temple inventories list offerings made to various Anunnaki figures. Administrative documents record resources allocated for their worship. Legal texts invoke divine witnesses, including Anunnaki members, to ensure oath-keeping and treaty compliance.

This documentary evidence reveals the Anunnaki as active components of lived religious experience rather than abstract theological concepts. Mesopotamian peoples built temples, appointed priests, allocated resources, and structured political authority around their understanding of divine cosmic order. The Anunnaki provided crucial ideological framework for these practical activities.

Archaeological excavations at sites like Ur, Babylon, and Nippur have uncovered physical evidence of this religious practice: temple foundations, cultic objects, inscribed votive offerings, and administrative archives that document centuries of continuous worship. The material record confirms what textual sources suggest—the Anunnaki represented vital elements of functioning religious systems that shaped daily life across ancient Mesopotamia.

Historical Development and Change

Understanding Anunnaki concepts requires tracking their evolution across more than two millennia of documented history. Early Sumerian god-lists from the third millennium BCE present relatively simple categorizations that become increasingly complex during subsequent periods. Old Babylonian literature expands Anunnaki roles across multiple genres—mythological, liturgical, and administrative. First-millennium syncretistic texts demonstrate how established theological categories adapted to changing political and cultural circumstances.

This developmental trajectory reveals sophisticated theological thinking that could accommodate change while maintaining continuity. Rather than rigid dogma, Mesopotamian religious tradition exhibited remarkable flexibility that allowed local innovation within broader frameworks of meaning. The Anunnaki concept survived precisely because it could evolve with changing circumstances while preserving core functions.

Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian texts show how imperial expansion affected divine categorizations. As Mesopotamian political influence spread across the ancient Near East, local deities became incorporated into established theological frameworks, sometimes appearing as Anunnaki members. This process demonstrates how religious categories served diplomatic and administrative functions beyond purely theological concerns.

Significance for Understanding Ancient Thought

The Anunnaki concept illuminates fundamental aspects of ancient Mesopotamian worldview. Their consistent portrayal as divine councils reveals sophisticated thinking about governance, legitimacy, and cosmic order. Ancient peoples understood authority as requiring deliberation, consensus-building, and procedural legitimacy—concepts that appear both in divine assemblies and earthly political institutions.

This theological framework also demonstrates remarkable intellectual sophistication in addressing perennial human concerns: Why do some rule while others serve? How should communities organize themselves? What relationships should exist between earthly and cosmic authority? The Anunnaki provided conceptual tools for addressing these questions within specific cultural contexts.

Moreover, studying Anunnaki references across different genres reveals how ancient peoples distinguished between various types of religious discourse. Liturgical texts, mythological narratives, administrative documents, and royal inscriptions each employed different literary conventions for discussing divine matters. This generic sophistication challenges assumptions about ancient intellectual capacity and demonstrates the complexity of early religious thought.

Contemporary Relevance and Scholarly Method

Modern scholarly approach to Anunnaki materials demonstrates the importance of contextual understanding in interpreting ancient sources. Rather than imposing contemporary categories or expectations upon ancient texts, effective analysis requires careful attention to original linguistic, cultural, and historical contexts. This methodological principle extends far beyond Mesopotamian studies to all encounters with historical materials.

The popularity of alternative interpretations also highlights the continuing human fascination with questions of cosmic purpose, divine authority, and humanity’s place within larger orders of meaning. While ancient astronaut theories misunderstand specific textual evidence, their popularity reflects genuine human concerns that ancient peoples addressed through sophisticated theological thinking.

Academic study of Anunnaki concepts continues to evolve as new texts are discovered, translated, and analyzed. Recent archaeological work has uncovered previously unknown archives that expand our understanding of regional variations in divine categorization. Digital humanities projects now allow comprehensive analysis of term usage across thousands of cuneiform texts, revealing patterns invisible to earlier generations of scholars.

Conclusion: Lessons from Ancient Wisdom

The Anunnaki represent far more than exotic deities from humanity’s distant past. Their conceptual development reflects sophisticated ancient thinking about governance, cosmic order, and divine authority that addressed perennial human concerns through culturally specific frameworks. Understanding these concepts in their proper historical context enriches our appreciation for ancient intellectual achievement while providing perspectives on contemporary questions of authority, legitimacy, and social organization.

Rather than seeking literal historical events behind mythological language, we discover greater value by approaching these texts as windows into ancient worldviews. The Anunnaki functioned as theological tools that helped ancient peoples understand their place within cosmic order and organize their communities according to divine models of governance.

This historical understanding offers more compelling insights than sensationalized misreadings because it reveals the true sophistication of ancient religious thought. Mesopotamian peoples developed complex theological systems that balanced flexibility with stability, local variation with universal principles, and divine authority with human agency. These achievements deserve recognition as remarkable intellectual accomplishments that continue to inform our understanding of early human civilization.

The clay tablets that preserve Anunnaki references represent humanity’s earliest sustained attempts to think systematically about cosmic order and divine governance. By approaching these materials with appropriate scholarly rigor, we honor both ancient intellectual achievement and our own responsibility to understand the past accurately. In doing so, we discover that truth verified through careful analysis proves far more fascinating than fiction imposed through wishful thinking.